Only Province in the Dark: Inside Newfoundland and Labrador’s broken ethics system

Full article available on the Independent.

Ann Chafe is the province’s acting Commissioner for Legislative Standards. Facebook. Illustration by Justin Brake.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE ON THE INDEPENDENT

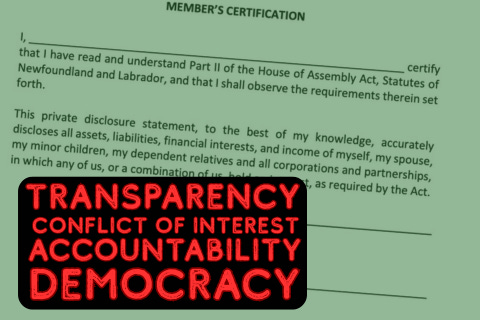

Every Canadian province has readily-available public disclosures, a transparency resource commonly used by journalists and the public to monitor politicians’ potential conflicts of interest — except Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Independent spent over a year working to acquire the Members of the House of Assembly (MHA) disclosures. In every other province, without exception, ethics disclosures are readily available online to every single member of the public. In this province, no ethics disclosures are posted online and there are significant barriers to accessing them since access is at the discretion of the commissioner for legislative standards and typically requires visiting the office in St. John’s.

Newfoundland and Labrador’s laws around disclosures were last amended in 2001, before the internet became the cultural and communications force it is now. The federal government first adopted online publication of its conflict of interest declarations in 2006, and updated them nine times since then with the intention of modernizing the availability and use of the conflict of interest disclosures.

Ontario was the first province to start using an online database, but all provinces have made an effort to ensure information is available online. The most recent, Manitoba, made its conflict-of-interest disclosures available online in 2023. Making conflict-of-interest disclosures publicly available online is a form of accountability, encouraging civic participation and allowing residents and journalists to research their elected officials.

When The Independent spoke with Newfoundland and Labrador Acting Commissioner for Legislative Standards Ann Chafe, there seemed to be resistance to making the disclosures available online. “There’s a line between privacy and what the public should know,” Chafe said in a phone interview last April. “Once you put anything online, it’s out there forever.”

Provincial law gives the commissioner control over what information is publicly shared. The law does not guarantee public access to information, leaving journalists and residents with limited recourse. This is entirely legal and rooted in a system that hasn’t been updated to reflect modern realities, such as the development of the internet as a source of accessible information.

Chafe was appointed acting commissioner in December 2022 after former commissioner Bruce Chaulk’s controversial six-year term ended. “Go and read the legislation. The legislation talks about how the public disclosure statements will be held; I have [them] here in a book,” Chafe during the phone interview.

The legislation mandates disclosure but hasn’t been adequately updated since its initial publication in 1995. The only way to ensure access is to visit in person and request to view the documents. With the information being more difficult to gather, compared to other provinces, journalists or residents may not understand all of the possible conflicts of interest in the House of Assembly.

The purpose of the disclosures is to serve as a mechanism within the government that aims to keep MHAs accountable. “The point of having these disclosures is me,” Chafe explained. “If they don’t satisfy my standards, I report them to the speaker, and the speaker chooses how he approaches it.”