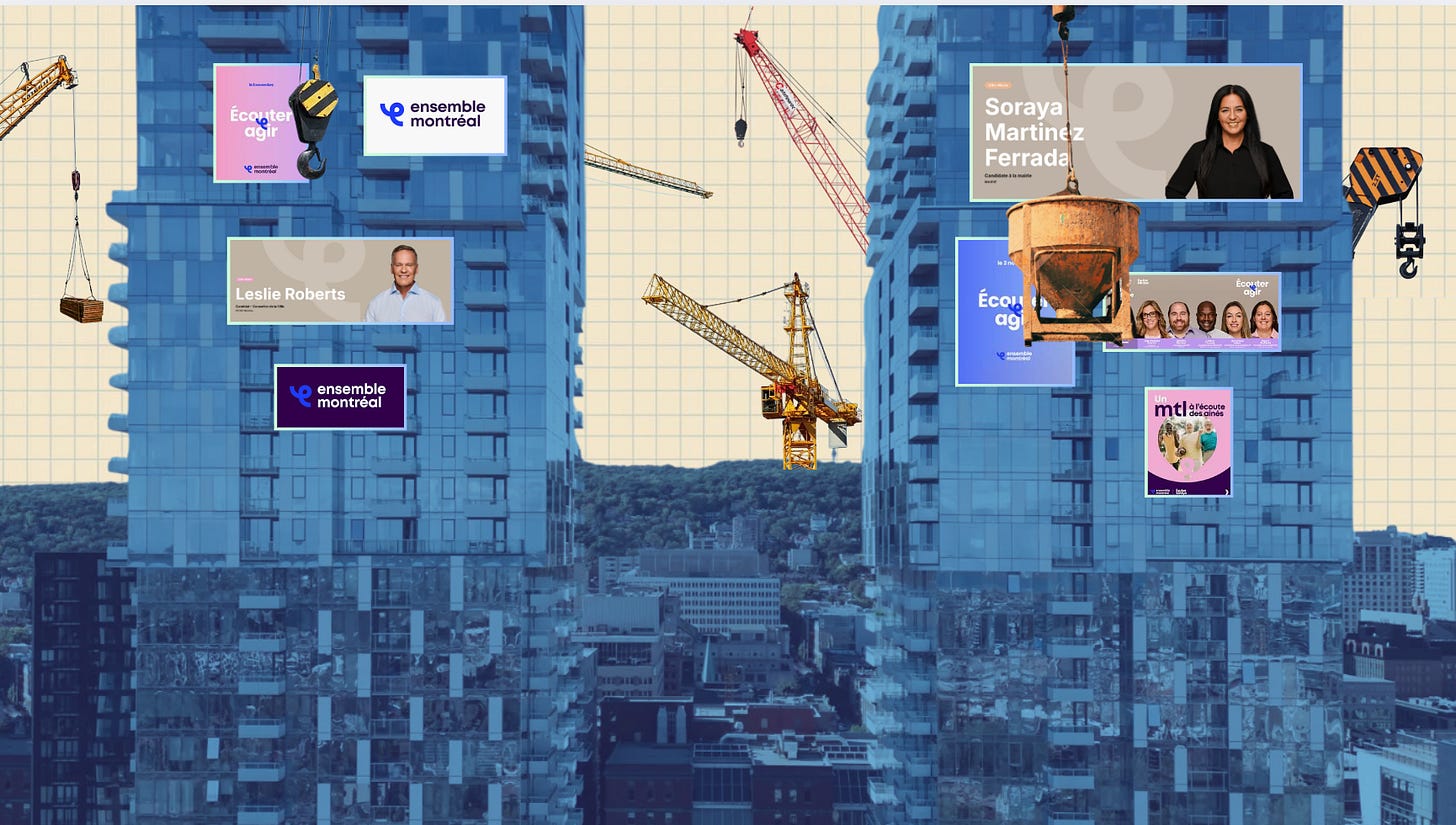

Municipal Election: Will Ensemble Montreal Fight for Tenants or Developers?

Soraya Martinez Ferrada wants to be “the housing mayor” while surrounding herself with Montreal’s biggest developers

THIS STORY WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN ENGLISH ON THE ROVER AND EN FRANÇAIS SUR PIVOT

In a city where 63 per cent of the population is made up of renters, tenants’ rights groups worry about Soraya Martinez Ferrada’s connection to developers and the ultra-wealthy.

On Sept. 30, the developer and frequent Conservative donor Ian Quint hosted a cocktail party featuring Martinez Ferrada on the roof of the old Holt Renfrew building. Quint’s company, Brasswater Inc., owns and manages 13 million square feet of commercial property across Quebec.

That night, Martinez Ferrada was introduced by billionaire Stephen Bronfman and the party was well attended by the “who’s who” of Montreal’s business establishment.

In June, she was similarly a guest at the 45th anniversary of CORPIQ, a landlord lobbyist group, along with colleague and city counsellor Julien Hénault-Ratelle. CORPIQ opposes implementing a rental registry in Quebec, and advocates for damage deposits, a practice that many landlords participate in regardless of it being illegal. Martinez Ferrada says that she wants a rental registry implemented. This would require participation by the provincial government.

In May, the Journal de Montréal broke the story that Martinez Ferrada herself asked for a $2,850 deposit from her tenants upon renting the house, which is illegal under provincial law. Martinez Ferrada responded to the report saying that she only took $1,000, and that the situation was entirely due to a real estate agent she had trusted to do the listing on her behalf. She says she returned the money.

An investigation by The Rover found that, during her tenure as a Liberal MP, Martinez Ferrada accepted donations from developers whose projects played a role in driving up commercial rent prices across Montreal.

Two years ago, Stephen Shiller — a real estate magnate — donated $850 to Martinez Ferrada. Shiller’s firm, Shiller-Lavy, used rental hikes to drive out small businesses from its properties in the Mile End before flipping the buildings at a massive profit.

During her time in the Trudeau government, where she worked as the Parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Housing, she received campaign donations from Labid Aljundi and Majd Al Jundy, whose firm built La Tour Fides, a 300-unit luxury condo tower in Montreal’s Quartier des spectacles.

Last year, Labid Aljundi decried the city’s lack of vision after he failed to get the green light for a six-storey condo tower that would have been built next to the REM station in Pierrefonds-Roxboro.

“We don’t get the impression that Ms. Soraya Martinez Ferrada is truly interested in the concerns of tenants,” said Véronique LaFlamme, spokesperson for the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain (FRAPRU). “If she is elected mayor, will she work for those who profit from housing or for the Montreal population, who, let’s remember, are mostly tenants?”

When confronted with the names of people who’ve donated to her, and the parties she’s been attending with these developers, Martinez Ferrada replied, “I believe it’s an error to believe we can’t meet with housing developers.”

Housing is set to be the defining issue in the Nov. 2 election, with some 48 per cent of voters telling pollsters it is their top priority. The only issue that came close, in the August poll, was homelessness, which is also a housing issue. As the price of rent in Montreal has nearly doubled in the last decade, the city has seen a surge in its unhoused population and the rise of homeless encampments. Scenes of human suffering are a daily reality in most central boroughs. 85 per cent of Canadians are living paycheque to paycheque, and only one in 10 Canadians feel that their wage covers their basic living expenses. Consumer debt is rising at an alarming rate.

We asked Martinez Ferrada how her government would achieve the ambitious targets set by her party: 50,000 new homes to Montreal in the next four years, including development of 10,000 social housing units, 6000 family units, 2000 student units, and 6000 affordable units. Martinez Ferrada did not seem aware of these numbers, despite it being on Ensemble Montreal’s website.

“I don’t even know where you got those numbers from, because (we) don’t have them in Ensemble,” she said. “What I announced was 2,000 transitional housing units.”

But is it realistic to imagine that working with the housing industry will yield 10,000 social housing units, 6,000 family housing units and 6,000 affordable housing units, as the party’s plan suggests? One housing expert has reservations.

“At one point, the government had the capacity and the resolve to stand against private development,” Ricardo Tranjan, author of The Tenant Class and researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, said.

“Instead, what governments do now is to engage in these long negotiations on a case-by-case basis with developers and try to nudge and squeeze a bit of community benefit here and another project there.”

Martinez Ferrada says she believes that regulations such as the bylaw for a diverse metropolis, also known as the 20/20/20 law, wouldn’t work because it would push developers to build housing outside of Montreal. The bylaw mandates that in large new residential developments, at least 20 per cent of units must be social housing, 20 per cent must be affordable housing, and 20 per cent must be family housing (i.e. three-bedroom or more), and in failing to build to these regulations, the developer could pay a modest fine. Ensemble Montreal has vowed to abolish the law if elected, with no replacement proposed.

The law has produced few affordable or socialized housing units, since almost all developers opted to pay the fine.

“I’ve met a lot of real estate developers throughout my life,” Martinez Ferrada said. “Because I myself worked to set up three housing cooperatives in my lifetime — since my family and I lived in housing that wasn’t suitable for my brother, who is disabled. So I’ve contributed a lot, and I really believe we can think differently about how we build in Montreal.”

In reality, partnering with private corporations is nothing new to Canadian governments.

Since the 1980s, under Brian Mulroney, Private-Public Partnerships (P3) have been the de facto method of building infrastructure throughout Canada. Tranjan explained how expertise in the government has shifted from the capacity to manage, coordinate, and finance complex projects to making P3s.

“There’s an entire generation of public servants that have been engaged in P3s their whole lives. And so that’s how they do it,” he said. This is despite many studies showing that privatization usually results in the use of lower-quality building materials while still costing significantly more.

As Martinez Ferrada has developed her relationships with developers, she has not met with tenant unions under the FRAPRU umbrella or The Coalition of Housing Committees and Tenants Associations of Quebec’s (RCLALQ).

Laflamme, spokesperson for FRAPRU, said that they sent two letters to Ensemble Montréal to propose a meeting in order to “present their concerns and priorities,” and that they hadn’t received a response to either letter.

When asked if she had met with advocacy groups, Martinez Ferrada said she had spoken to groups that “focus particularly on homelessness.” The Rover asked if she had seen the letter sent by FRAPRU and their members.

“We probably saw it, I can’t tell you if we answered or not,” she said, unsure of the exact letter in question. “But some of my team met with them, like Benoit Langevin.” Langevin is a current member of the city council for Ensemble Montreal.

Laflamme categorically rejected having met with any individual within the party.

“We have not had any meetings with Ensemble Montréal, especially not since Madame Martinez Ferrada became leader,” she said.

A representative for RCLALQ confirmed that they received a response to a letter they sent to meet with Martinez Ferrada, but no formal meeting has been scheduled or taken place.

Martinez Ferrada told The Rover on October 4th “there are still 28 days left in the campaign” and that she’d be “pleased to meet them, no problem.”

Using her conflict of interest records from her time in office, we narrowed down the number of properties the mayoral candidate owned. We confirmed the properties with Martinez Ferrada, who spoke openly about her investments.

She was in possession of two rental properties — one in Hochelaga, one in Saint-Michel. The properties she owned for her own use were a chalet in Montpellier, and her house that she lives in.

She has since sold the condo in Hochelaga and is trying to sell her chalet. Her tenants in Saint-Michel are a family with three kids who “pay about $2,850 for the entire house, and they haven’t had a raise (in rent) since they moved in,” she said. The family has lived there for three years.

Martinez Ferrada has generally lived in Montreal since she moved here with her family as a child. An investigation by The Rover showed that her primary residence was, until recently, in Longueuil. Martinez Ferrada was not on Montreal’s initial voting registry list, indicating she recently moved back to the island.

When asked whether she moved to Montreal exclusively for the mayoral race, Martinez Ferrada defended her bona fides as a Montrealer.

“I fell in love with someone who has a child who’s finishing school, and I didn’t want to take him out of his environment. So I moved with him,” Martinez Ferrada said. She says she only lived in Longueuil for a year, and when she decided to run for municipal office, she moved back to the city.

“No one’s ever doubted that I’m a Montrealer.”

The candidate has come under fire for her stance on Airbnb as well, though she said that she feels the media portrayal of her comments was inaccurate. Her original comments that were reported on were her expressing her desire to counter the marketing of housing for short-term rental purposes without penalizing citizens who want to “top up their income at the end of the month.”

“I’m against the commercialization of housing on the back of the housing crisis by companies and private investors,” she said. “We must ban more, but not only that, we need to be able to apply the regulations put in place.”

She pushed back against the bylaw that Projet Montréal has implemented, calling it a “public relations move” instead of a regulation that wants to deal with short term rentals. Her solution is virtually identical to Projet Montreal’s, but she would reduce the number of days during which owners can rent out their primary residence on a short-term basis from 93 to 90 days—consecutive or non-consecutive, and increase the number of inspectors to enforce the ban to fifty for the next two years.

While housing is bound to be one of the largest questions in this election, worries over rent and affordability are growing across Canada.

“I want to make sure that no one else falls into homelessness,” Martinez Ferrada said. “We have to do prevention. The laws are so harsh that people, if they have bad luck, can’t pay their rent, they can lose their home.” So she presents herself as the “housing mayor.”

On Nov. 2, voters will decide if that’s true.