Can Luc Rabouin and Projet Montréal Fix the Housing Market

After eight years under Projet Montréal, rent across the city has more than doubled. Why should voters believe things will change in a third Projet mandate?

VERSION FRANÇAISE ICI

Luc Rabouin, the new leader of Projet Montréal, says he does not believe it’s his party’s fault that rent in the city has more than doubled since it took power.

Projet Montréal won a second mandate in 2021 off the idea that a family shouldn’t have to “ruin itself” financially to live in this city. On July 1 of this year, there were over 200 households across the island without a place to live after their lease expired. Meanwhile, Montreal’s homeless population has increased by 10 per cent each year since 2018.

Though the party has delivered on some promises, producing hundreds of builds with UTILE, a company that builds social housing for students, renters feel stranded. Montrealers are suffering exponential rent increases, and moving isn’t an option, since if they leave their rent-controlled lease, their new apartment might double their rent.

While a majority of the city is dealing with these challenges, Rabouin is not. Citing a conflict of interest declaration filled by Rabouin in 2022 and provided to The Rover by journalist Zachary Kamel, we asked Rabouin about his investments.

He told The Rover that he has owned a duplex for more than 20 years and is a landlord. His neighbour/tenant pays $905 a month. This was confirmed by a source close to Rabouin. Rabouin says that he and his tenant have an excellent relationship, and Rabouin has opted not to increase her rent for some time.

Rabouin rejects the idea that being a landlord and a house owner harms his credibility to manage the housing crisis in Montreal.

“I’m not a big property owner, I’m not an investor, I’m a landlord-tenant,” he said.

On top of owning his house and being a landlord, Luc Rabouin makes $177,309 after taxes, four and a half times the median wage of $39,000 for Quebecers.

“Rent has increased exponentially everywhere in Quebec and Canada, not just Montreal,” Rabouin said. In his view, it is the rent control laws in Quebec that have failed renters. “If the rent has gone up this much, it’s because rent control laws aren’t working.”

Despite Rabouin asserting that this phenomenon was across the whole country, it isn’t true that other cities have experienced the same price increase as Montreal.

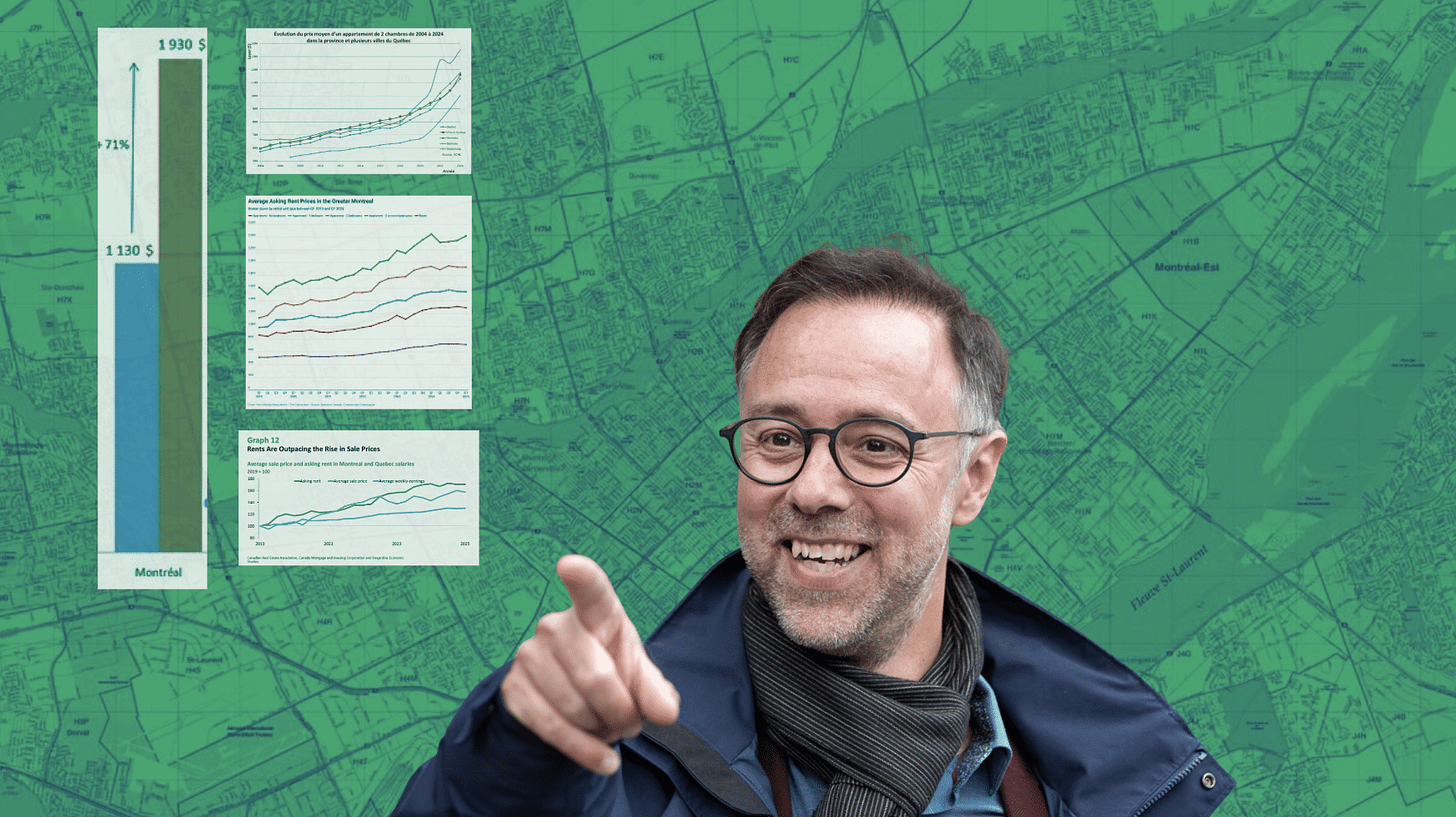

By comparing the average rent paid in 2017 versus 2024, the average rent in Montreal has gone up 120 per cent since Projet took power: rising from $783 to $1,724. Although the crisis is affecting other cities, rent did not increase to the same degree as Montreal. Quebec city in 2017 was more expensive than Montreal, and yet in 2024 had only increased by 63 per cent, half the percentage increase of Right now, if a Montrealer moved, the average asking rent to move into an apartment is $1,930, representing an increase of asking prices in the city of 71 per cent since 2019, according to Statistics Canada. Certain factors may explain this– Montreal is catching up to other big cities in Canada, it’s the job hub of the province, but this alarming increase can be circumvented through social housing.

Rabouin said that his party can nonetheless help to bring back affordability by building out the socialized housing stock, a promise that Projet hasn’t fulfilled for the better part of the past four years.

During Mayor Valérie Plante’s second mandate, the party implemented the bylaw for a diverse metropolis, also known as the 20/20/20 law.

The bylaw mandates that in large new residential developments, at least 20 per cent of units must be social housing, 20 per cent must be affordable housing, and 20 per cent must be family housing (i.e. three-bedroom or more). Developers can choose to pay a modest fine if the new construction does not meet these requirements.

The party’s rhetoric on the legislation was fairly boastful. Upon introducing this bylaw, Plante called it the “most powerful in North America.” The bylaw has been widely acknowledged as not living up to the promise.

According to the data available on the city’s own website, the bylaw led to five projects including on-site social housing, and three off-site. The amount of housing units which were created in these projects is unclear, as some don’t have addresses in the file.

Rabouin thinks the bylaw is too complicated.

“It’s too hard to apply,” he said. “Developers prefer to pay the fine, because then they don’t have to create the units.”

He wants to simplify the law. The party’s solution would be to make it obligatory to build 20 per cent off-market housing and to make better use of the money collected from the developers. The law has collected $58 million in fines.

“We can’t ignore $58 million, but there’s still some big failures around the implementation of that law,” said Stéphan Gervais, expert in Quebec politics, and scientific coordinator for the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research on Montréal at McGill.

Gervais commented that despite these failings, Rabouin seems determined to stand by the law, with a few adjustments.

Despite having an additional $58 million in the coffers, Rabouin does not want the city to become a landlord or developer itself. “Housing is created either by private developers or non-profit developers. The city supports it,” he said. Instead, they want to support the building of socialized housing through zoning laws and financial contributions.

Ricardo Tranjan, author, housing expert and researcher for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, believes that this attitude places all of the cards in the hands of the developers.

“Governments (need to) get back into it, and have the capacity to develop more non-market housing,” he said. When developers won’t cooperate, he believes that governments need to say, “We’re gonna take back the land and put that shit out ourselves.”

Though the bylaw for a diverse metropolis has been ineffective, the new regulations around Airbnb, introduced this year, have yet to prove themselves. In a bylaw which took effect as of June 10th, AirBnB is only permitted 3 months a year in Montreal, from June 10th to September 10th.

Tranjan says enforcing a half-step regulation like the 9-month-a-year ban will be challenging.

“To enforce that is extremely difficult,” he said. The most famous application for short-term rentals is Airbnb, but many other short-term rental apps exist. Booking and Expedia offer short-term rentals, as well as 9flats, Craigslist, or Kijiji. Enforcing it on Airbnb will be hard enough, but access to other platforms means that many may simply sidestep the ban.

Controlling one app might work, but what happens when landlords begin using alternative platforms that are being ignored by governments, and they don’t have the capacity to enforce across a wide range of platforms like this?

One solution Tranjan proposed is an “enforcement fee.” When people break the rules, a fine is issued, which is put back into the system to pay enforcers. This creates a system that won’t cost the city more money to hire personnel. This still might not be sufficient, however.

“How do you cover the entire territory of Montreal, or Toronto, or Vancouver?” he said. These sprawling, massive cities wouldn’t be simple to control. Studies have shown that the only truly effective action is to have a full ban on Airbnb.

“If this is a full unit (an entire apartment or house, not just a single room in an apartment), it needs to be rented long term. If it’s not, maybe then you can rent it short term,” said Tranjan.

A recent poll has shown that 55 per cent of Montreal residents are dissatisfied with Plante’sadministration.

Can Luc Rabouin stand in a year when Montrealers seem poised not to vote? It seems that disillusioned voters might be the biggest voting bloc in this year’s election, with a recent poll saying 37 per cent aren’t decided.

“Will he truly be able to take responsibility for the actions of Projet Montréal because he was present, but at the same time distance himself from it and say, ‘I am a renewal; I am capable of bringing new ideas?” Gervais said.

On Nov. 2, the city will decide.

With files from Zachary Kamel

He should be able to say that the party did good things. Throw the old administration under the bus (sorry but whatever it takes to win) and say that the other parties will not go far enough or are incapable of getting things done. Don’t play nice! Just win!